|

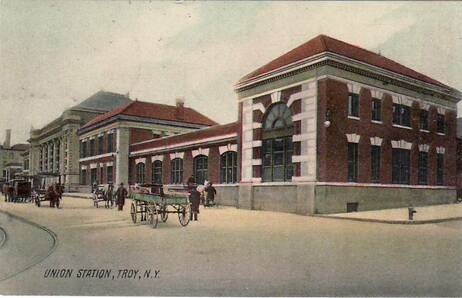

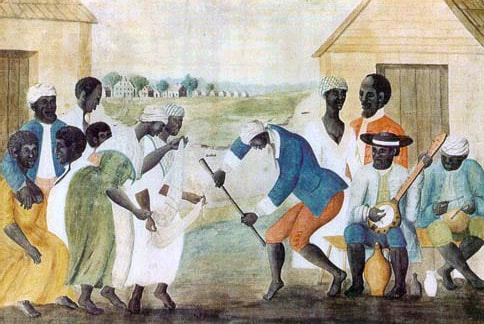

2/12/2019 0 Comments The Rescue of Charles Nalle The following is my retelling of one of Troy's greatest stories: The train from New York City rolled into Troy’s Union Station on a hot August 9th, 1932 and opened its doors to release its passengers. Among them was an older, well-dressed African American man, tall, slender and fair-skinned. He was 72 years old, a recent widower who was travelling alone, carrying a suitcase and his hat. His train ticket from Washington, DC, announced his destination as Saratoga Springs, less than an hour’s trip to the north. His name was John Charles Nalle, recently retired from the Washington, DC school system, where he had started as a teacher, and retired as the Superintendent of Colored Schools. He was stopping in Troy on his way to a summer vacation in Saratoga, but because he had once lived in Troy as a boy, he had accepted an invitation to see his old home. Greeting him at Union Station was Garnet Douglass Baltimore, Troy’s most distinguished and famous African American citizen. Mr. Baltimore was the first black graduate of Troy’s prestigious Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. A successful civic engineer, his legacy to the city was his design of Prospect Park, Troy’s largest and most beautiful public park. Unlike most African Americans of his day, he was respected and accepted in both board rooms and black churches. Garnet Baltimore’s father had been a friend of the Nalle family during their stay in Troy, long ago, so as the surviving sons of their fathers, Garnet and John met at the train station – two old black men who hadn’t seen each other since they were small children. To John’s amazement, their reunion was also being covered by the press. The Troy Times had dispatched a white reporter who was eagerly awaiting the chance to interview Mr. Nalle. Nalle wondered why the press was there. Garnet Baltimore was a prominent citizen, but it still made very little sense. Who would care if two old black men met and reminisced? “Let me show you something, John,” Baltimore said. “We’re going to visit a place that was quite important to your father.” They got into a car and rode down the hill to the center of the city. The reporter followed. The car stopped at the corner of First and State Street, only blocks from the river, in the heart of what was once Troy’s banking district. At the north-east corner of the street stood a four-story red brick and limestone mid-19th century building which had been built for the Mutual Bank of Troy. A large brass plaque was affixed to the building’s side. Baltimore guided his guest to the wall so that he could read it. “Here was begun on April 27, 1860, the Rescue of Charles Nalle, an escaped slave who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act.” John Nalle turned to his friend in shock. “What? I’ve never heard a word about this,” he exclaimed. “Well, my friend,” said Garnet Baltimore, “Have I got a story to tell you!” He guided him to a shady spot by the wall. “It all starts in Culpepper County, Virginia.” The Hansbrough Family of Culpepper County Peter Hansbrough was a member of one of Virginia’s oldest families. His aristocratic British ancestors settled in the colony in 1639. By the early 1800s they were one of the state’s largest and wealthiest landowners, their holdings well-tended by African bondsmen and women. Hansbrough was known locally as quite the elegant dandy, a man who still loved powdered wigs, as well as gambling, fox hunting, fine wines and liquors, and nights of wild carousing. Much of his carousing was done with the women who were his property. He prided himself as a connoisseur of both horseflesh and human flesh, and enjoyed his attentions on women, whether willing or not. One of his conquests was a young enslaved woman named Lucy, who was the daughter of a similar union of white master and black slave. Lucy had four children. Her youngest, whom she named Charles, was Peter Hansbrough’s child. He was born somewhere around 1821. Hansbrough’s longsuffering wife Frances, the daughter of a neighboring planter, bore him nine children. The youngest, Blucher, was about four years older than Charles. The two boys grew up together, so resembling their father, and so alike in appearance that outsiders would not have known one child was master, the other, a slave. But as they grew older, that difference was made quite clear. Blucher was sent off to be educated and raised to become a master of men, Charles was not allowed to learn to read or write and was sent to the stables. He found his calling in horses and became an expert trainer and handler. He was a “horse whisperer” of the first order, and as an adult, was often called upon to work with the horses on other plantations. He became the Hansbrough family’s coachman, and often went on overnight trips with the family – his family, although no such admission was ever made. Charles accompanied his father to horse races and cock fights, watched him drink, gamble and carouse, and no doubt spent many a night tucking the old man back into his carriage, bringing him home to his wife and bed. Hansbrough also took his youngest son with him on many trips, and young Blucher grew up to be just like his father, only worse. Peter Hansbrough died of his excesses, and Charles and his family were among the holdings left to Blucher in his will. With eight siblings ahead of him, Blucher’s household took up residence at one of the family’s many farms in Culpepper County. Charles was valuable property, and in the tradition of upstanding Virginia landowners, was kept in fine clothing, driving an elegant rig with a fine brace of horses. He ate well and was accorded as much liberty and reward as anyone could, considering they were owned by someone else. He lived in a cabin away from the main house with his mother, sisters and brothers. When he wasn’t working with the horses, or driving, he was expected to perform chores around the grounds, and help with the agricultural needs as well. As a reward for fine service, he was allowed to court and marry an enslaved woman named Catherine “Kitty” Simms, who lived on a nearby plantation. Charles was in his early 20s when the couple “jumped the broom.” Allowing slaves to marry was a rare occurrence. Having a married couple on different plantations was purposefully done to prevent strong family bonds from developing. Despite that, Charles was able to obtain passes to visit Kitty, and the couple had two children while they were all in captivity. It was sometime during his early years of marriage that he was given the surname “Nalle,” the family name of his mistress, and a well-respected name in Culpepper County. Frances Nalle Hansbrough’s father had certainly spread his seed around as well, so it may have been an effort to diffuse the obvious links between Blucher and Charles. The two men were no longer children. Despite their filial relationship and physical resemblance, Blucher was master; Charles forever would be slave. Blucher embodied the ideal picture of a young, handsome and wealthy Virginia planter. But underneath the façade of respectability and tradition was a spoiled youngest son who had no business sense, little purpose and limited sense of propriety. His overseers and slaves ran his farm, leaving him time to spend his days at the racetrack or cockfighting pit, in gambling halls, brothels or on the pallets of his chosen women in the Quarters. Back at the house, the servants all overheard conversations and arguments between Hansbrough and his wife and creditors that led them all to believe that Blucher was in financial trouble, and that they were all only a bad poker hand away from being sold to pay off his debts. No one on the Hansbrough farm ever really felt safe. Charles Nalle may have been just another slaver’s illegitimate son lost to history except for an event that took place in 1847. That year, someone set fire to one of Blucher’s barns. One of the male slaves was suspected. The entire population of the farm was gathered and questioned. When no one confessed, Blucher randomly picked from the men and had Charles, his three brothers and two field hands rounded up, chained, and sent to Richmond for auction. There was no evidence against any of them, and the cries and tears of their families fell on deaf ears. As the men were being carted away, Kitty came running through the fields, her feet bleeding from the newly cut hay. She pleaded with Blucher not to sell her husband, but he threw her to the ground, and drove away. Once in Richmond, the men were jailed, and sent to the auction block several days later. The two field hands went for less than what Blucher expected, and when the four light-skinned brothers went before the crowd, there was a great hesitation to buy them. Light skinned men with white features were potential trouble, even a man as highly skilled and well-known in Virginia as Charles. Their presence on the block also made the buyers uncomfortable. No one bid on them. They were taken back to the prison, where Blucher abruptly announced that he was taking them back to his plantation. There would be no sale. He hoped that a memorable lesson had been learned. During the wagon ride back to Culpepper County, Charles had time to examine his life. If he had previously thought that his days in slavery were tolerable, he no longer had that illusion. His skill with horses and the rewards he had been given had convinced him that he was too valuable to ever be mistreated or sold. Perhaps he thought his relationship to the Hansbrough’s would protect him. He realized that he couldn’t trust Blucher – his elder brother, his almost-twin. Blucher would obviously rip him from his world and his family in an instant. The fires of freedom may have been barely warm coals before, but now they were smoldering embers. Charles would be free. In 1855, Kitty’s owner, Colonel Thom died. He left a lot of debt behind him, and as a result, his widow and family saw the need to tally up the worth of the estate, including the slaves, and downsize. Many assets, including some people would be sold. Eighteen slaves would be granted manumission. Among those freed were a pregnant Kitty, her four daughters and her sister Jenny. Virginia was cracking down on its free black population due to rising fears of insurrection and slave revolts. Violent border wars had erupted in Kansas over the issue of slavery, with hundreds dead. The Anti-Slavery movement up North was actively hindering slavers and helping escapees reach Canada. They were turning the public against slavery and emboldening the South’s blacks to throw off their chains. Every Negro was suspect, so the sisters and their children took up residence in Washington DC, then called Washington City. The nation’s capital was a slave-holding territory, but it allowed free blacks to live there, provided they carried their manumission papers with them at all times. Kitty and her sister Jenny, who was married to a man named James Banks, chose Washington because it was as close to their husbands as they could get. As it was, their men were still two hours away by train. Life went back to normal at Blucher Hansbrough’s farm. After everything settled down, Charles was occasionally allowed to travel to Washington to visit his family. If anyone realized that he was not white, or free, his papers, which he was unable to read, revealed his legal status. By 1858, Blucher’s profligate lifestyle was catching up to him. The larger economy was failing, his operating costs were going up, and he was drinking heavily. He found solace in wild gambling outings where he lost even more money. He was in grave danger of having to sell his farm to pay his debts. In an effort to make some money, Charles had been renting himself out, with Blucher taking the lion’s share of the payment. Despite that, he saved a decent amount of money, but when he approached Blucher with money to buy his freedom, he was roughly rejected. Hansbrough refused to let him go. He also took the money that Charles had saved. Charles was allowed one more trip to Washington City to visit his wife in February of 1858. Kitty got pregnant again that weekend. When he returned, Blucher told Charles it was time he found another woman, Kitty was too much trouble, and Blucher was not going to allow any more trips to Washington. Charles held his temper and his peace but vowed to himself that that was the last indignity he would suffer. He would be free, or he would be dead. The conclusion of this story will be posted tomorrow. My research for this story comes from the Troy Times, the Auburn Citizen, and information gathered on various websites, much of which is gleaned from the scholarship of Scott Christianson, the author of a very highly researched and detailed book on the subject called “Freeing Charles: The Struggle to Free a Slave on the Eve of the Civil War”. Mr. Christianson’s book was especially helpful with details about Charles Nalle’s early life and the people and places that made up his world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Suzanne Spellen. I've been many things: a writer, historian, preservationist, musician, traveler, designer, sewer, teacher, and tour guide; a long time Brooklynite and now, a proud resident of Troy, NY. Archives

February 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed