|

6/8/2020 12 Comments Enough, No More When I was a child in the 1960s, it seemed that everyone smoked. Cigarettes were everywhere in American society. Tobacco companies not only had ads for their products in magazines and on billboards, but they sponsored radio and television shows, and funded charitable and sporting events. Cigarettes were relatively cheap, and if you couldn’t afford them, you could roll your own from loose tobacco for even less money. Big Tobacco made their product available for anyone who wanted it.

Anyone who was anyone smoked. Movie stars, politicians, musicians, the rich, the factory worker, the poor. No one questioned the health issues or even the aesthetics. People could smoke in the workplace, in restaurants and theaters, just about everywhere but church. There was nothing cooler than having a cigarette in your hands. Everyone wanted to look as elegant as Sophia Loren or Lauren Bacall, as cool as Bogart or Miles Davis, or dangerous and sexy as an international spy or Steve McQueen. From the Beat Poet to the Marlboro Man, the soldier on patrol to the sexy girl allowing a man to light her cigarette, there was no doubt that being a smoker made you a winner. Until it didn’t. My parents, like most adults, smoked. By the time I was in my very early teens, the dangers of smoking were now well-known. But both of them were now two-packs a day smokers, both addicted to nicotine just as millions of other people were, and still are. My brother and I wanted them to quit. I hated the smell, I hated that the accumulated nicotine turned everything yellow, and I hated seeing ashtrays everywhere, stuffed with stubbed out butts, smoked down to the filters. I hated riding in a car full of smoke. And I was terrified they were going to get lung cancer and die. We were pretty insistent and obnoxious about it until one day my Dad just up and quit. One day he was a smoker, the next day he wasn’t. He never went back. It took my Mom longer. She wanted to quit, but just couldn’t do it. She tried patches, even got someone to hypnotize her, but she couldn’t quit. The moment of truth came one night when she ran out of cigs and tore through the house looking for more. Like an alcoholic looking for liquor, she went through all of her purses and pockets, drawers, and boxes. She combed through the ashtrays looking for a butt that had enough tobacco left to get a couple of good drags, but there was no joy there. The stores were all closed. If she had been able to find a year old broken cigarette in the bottom of a purse, she would have smoked it like a drowning person reaching air. But there was nothing. The next morning, she emptied out all of the ashtrays, made sure she hadn’t missed anything, and never touched another cigarette again. She told us that she had reached that moment when she realized that these little rolls of flavored tobacco ruled her life. She didn’t like the angry, desperate person who tore the house apart. She was ashamed and embarrassed that we saw that. She had had Enough.

12 Comments

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Robert Frost (1923) Whose woods these are I think I know. His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow. My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year. He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound's the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake. The woods are lovely, dark, and deep. But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep. When I was in primary and secondary school, we had to memorize this poem, along with some of the other classics of American and English poetry. We learned a few famous monologues from Shakespeare, as well as fragments of Longfellow, Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth and Poe. Although it wasn’t taught in school, I also memorized poems by Langston Hughes and other African American poets that my wonderfully educated mother also loved. I’ve always appreciated and cherished the way words move us and have long been fascinated by both the power of words and the flow of poetry. That’s probably one of the reasons why I became a writer, always striving to have that flow myself – that wonderful superpower that is able to inspire, teach and move us to emotion and action. 6/19/2019 2 Comments In Praise of Walking ToursI recently wrote about the fun and importance of house tours, now its time to praise a much more common tour – the walking tour.

I’ve been going on walking tours for years. I’ve also been leading them for at least 12 years. There is no better way to learn about a city or town than to walk its streets and byways. Sure, you can drive around and admire any city, town or neighborhood, but you are often hurried along by traffic. If you are driving, especially in a new place, you need to be paying attention to the road, not the buildings, and you miss most of what you are trying to see. You can certainly get an idea of that area’s beauty or architectural significance by car, but nothing beats being able to put sneakers to the street and walking around with a knowledgeable guide. It’s an informative experience, an opportunity see detail and specifics, take some photographs, and it’s great exercise, too! Walking tours are not new. In this country, middle and upper class Victorians were really the first groups of people to have the leisure time to walk around. By the late 1800s, guidebooks were quite plentiful for most major cities, both foreign and domestic, and it wasn’t uncommon to see well-dressed people giving themselves self-guided tours all over. They also enjoyed guided tours. Those tours highlighted major monuments, buildings and homes and rarely strayed into unfamiliar neighborhoods or streets, but they were very popular to a group of people who prided themselves on being well-traveled and well-educated. Unfortunately, as a society, we seem to have lost that curiosity and the desire to KNOW. 5/26/2019 1 Comment In Praise of House ToursWhen my Mom and I first moved to Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, we hadn’t been in our house a month before someone knocked on our door, welcoming us to the neighborhood, and asking the question, “Would you be interested in showing your house in our annual neighborhood house tour?” The organization sponsoring the tour was called the Brownstoners of Bedford Stuyvesant, and they were very persuasive. Our house ended up on the tour in 1983. That was my first experience with house tours. The Brownstoners were (and still are) a community organization that was established in part to promote all that was beautiful and positive in a community that had been written off in the 1960s as the “biggest ghetto in America.” Bed Stuy has always had a large percentage of homeowners, and these proud people, who often worked two or three jobs in order to pay the mortgage, were proud of their homes. When society was failing around them, they lived ordinary, hard-working lives, like people do in most neighborhoods. They went to work every day, sent their kids to school, went to church on Sunday, and shopped in local stores. They swept in front of their homes, planted flowers in the yards, and watched each other’s kids. They kept the neighborhood together. This fact was generally forgotten in the stories about poverty, drugs and crime, and the ignorance of how people live. Bed Stuy is a huge neighborhood, larger in landmass than the entire city of Troy, with a larger population. Some parts were, and still are, better than others. Much like North Central, or South Troy, a neighborhood is much more than simply the deeds or conditions of those who fall short or turn to crime or drugs. There are always good people doing the best with what they have, and there is always beauty. Concluding the story of Charles Nalle: the rescue and aftermath. The slave catcher, Wall, and the Deputy Marshall stopped Nalle in the street, and arrested him. Before he knew what had happened, he was manacled and taken back to the reluctant U.S. Commissioner, Miles Beach. When Charles didn’t return from the bakery, Uri Gilbert’s son went out to look for him. He went to his landlord, William Henry, but Henry had not seen him since that morning. It was not like Charles to disappear, and William Henry, who knew Nalle’s history, suspected the worst. Henry was a member of the Vigilance Committee, a Troy abolitionist group that aided escapees in secret and spoke out against slavery and the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law in public. He made some inquiries, and quickly found out that Charles had been arrested and was in the hands of a slave catcher. With no time to waste, he sent the word out and told his people to get ready to act. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was a fine piece of evil legislation, with some especially nuanced advantages for the slave holder written into it. Not only could a slave owner or his or her representative come north and snatch a suspected escapee off the street, that person had no rights, and no recourse to prove that he or she was not a slave or was not even the person they were looking for. There were usually no photographs or sketches, as enslaved people were usually not the topic of art or photography. There were only vague descriptions which would match any number of people. This was fine with the slave catchers, because they got a bounty for each fugitive returned South. If they had the wrong person, it really didn’t matter, who would believe a slave? When Charles Nalle was brought before Beach, all the paperwork had already been prepared by Henry Wall, filled out days before he had even been captured. Nalle was not allowed to identify himself or testify on his own behalf or give any names for potential witnesses. His fate had already been decided. All that was needed was the formality of having Wall and the informer, Horace Averill, stand before the Commissioner and declare that Nalle was the fugitive Negro slave who had unlawfully escaped his enslavement, and run away. His lawful owner, Mr. Hansbrough, had just stepped off the train to meet them, and the fugitive would be taken back to Virginia, where he belonged. Charles was being held in the cells in the basement of the Commissioner’s office, in the Mutual Bank Building, on the corner of State and First Streets. A prominent Troy attorney named Martin I. Townsend quickly volunteered to be his lawyer. He went to the Commissioner’s office to represent his client, but it was already too late, the paperwork had been signed. Townsend rushed out to prepare a writ of habeas corpus to present to a judge, and thereby get a stay. Continuing the story of Charles Nalle and his escape from slavery:

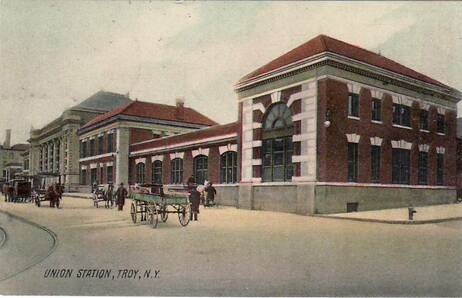

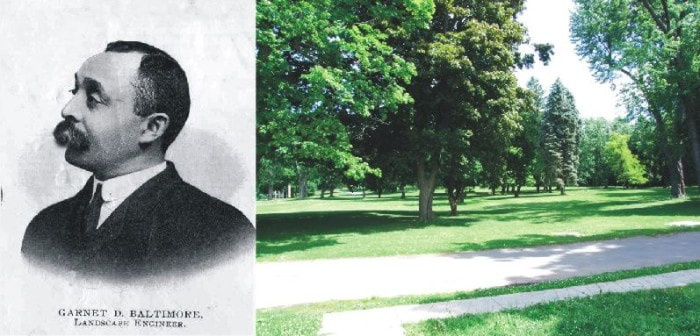

Charles’ travels as the family coachman had allowed him to mingle with all kinds of people over the years, both black and white. It’s unknown exactly when it happened, but one of the people he met was a young Northern tutor named Minot S. Crosby, the son of a New England Congregationalist minister. Crosby was traveling through the South, supporting himself as a tutor to wealthy families. For a time, he had tutored the son of one of Blucher Hansbrough’s neighbors. Unbeknownst to the planters, Crosby was also an ardent Abolitionist. Like a secret agent behind enemy lines, he found time to speak with the enslaved, passing along information about the Underground Railroad. His employers would have been furious to find out that young Crosby was in contact with Harriet Beecher Stowe and other New England Abolitionists, as well as more local agents. They would have killed him. Charles and his brother-in-law James Banks decided to escape together. Banks was a big man and had been a blacksmith for most of his life. Banks was not owned by Hansbrough, he lived on a neighboring plantation. Charles went to Blucher and asked to visit his wife one last time. He told him that Kitty was having problems with her pregnancy and may not survive. He begged to be allowed to see her. Blucher had his family in the Washington area look for Kitty to find out if that were true. Around the small world of Culpepper County, the state of Virginia was gearing up for the inevitable war between the North and South. Politics in Washington had deteriorated between slaveholding states and free. Congressmen were coming to blows on the floor of Congress over the issue of slavery, while on farms and plantations, people were escaping north in greater numbers, as Southern slaveholders tried to hold on to a way of life that was unsustainable. Charles Nalle probably knew little about that, but he knew his window of opportunity was shrinking. In the Quarters, people whispered that Blucher was on the verge of losing the farm and had spoken to others about selling most of his slaves to raise capital. It was now, or never. Charles spoke to his siblings about escaping. His brothers had married and were fathers. They did not want to leave their families and chose to stay put. But they encouraged Charles to go. In the fall of 1858, Blucher received word from his contacts in Washington that Kitty was indeed doing poorly. He decided to be magnanimous and allow Charles to have a one-week pass to Washington. He would be allowed to go with James Banks, and the two would take the baggage car of the local train to Washington. Blucher had to go to Richmond on business, so Charles and James would be watched by Hansbrough relatives who would be on the same train. The two men, with their meager luggage, and all-important travel passes, boarded the baggage car, and headed north to Washington. When they got there, the Hansbrough contacts were supposed to keep an eye on them, and make sure they went to their wives, but Charles and James blended into the crowds, gave them the slip, and never came near their families. They did not want to give law enforcement or their owners any indication of their wives’ involvement in their escape. They were able to contact one of the many representatives of the Underground Railroad, as given to them by Crosby, and go into hiding. When it became obvious that Nalle and Banks had escaped, Blucher Hansbrough was furious. He rushed back home from Richmond. The first thing he did was question Charles’ family, who feigned ignorance. In retaliation, he sold all three brothers “down the river,” further South, where slavery was much harsher, and conditions more dire. They were never able to be found again. Charles would carry that guilt for life. 2/12/2019 0 Comments The Rescue of Charles Nalle The following is my retelling of one of Troy's greatest stories: The train from New York City rolled into Troy’s Union Station on a hot August 9th, 1932 and opened its doors to release its passengers. Among them was an older, well-dressed African American man, tall, slender and fair-skinned. He was 72 years old, a recent widower who was travelling alone, carrying a suitcase and his hat. His train ticket from Washington, DC, announced his destination as Saratoga Springs, less than an hour’s trip to the north. His name was John Charles Nalle, recently retired from the Washington, DC school system, where he had started as a teacher, and retired as the Superintendent of Colored Schools. He was stopping in Troy on his way to a summer vacation in Saratoga, but because he had once lived in Troy as a boy, he had accepted an invitation to see his old home. Greeting him at Union Station was Garnet Douglass Baltimore, Troy’s most distinguished and famous African American citizen. Mr. Baltimore was the first black graduate of Troy’s prestigious Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. A successful civic engineer, his legacy to the city was his design of Prospect Park, Troy’s largest and most beautiful public park. Unlike most African Americans of his day, he was respected and accepted in both board rooms and black churches. Garnet Baltimore’s father had been a friend of the Nalle family during their stay in Troy, long ago, so as the surviving sons of their fathers, Garnet and John met at the train station – two old black men who hadn’t seen each other since they were small children. To John’s amazement, their reunion was also being covered by the press. The Troy Times had dispatched a white reporter who was eagerly awaiting the chance to interview Mr. Nalle. Nalle wondered why the press was there. Garnet Baltimore was a prominent citizen, but it still made very little sense. Who would care if two old black men met and reminisced? “Let me show you something, John,” Baltimore said. “We’re going to visit a place that was quite important to your father.” They got into a car and rode down the hill to the center of the city. The reporter followed. The car stopped at the corner of First and State Street, only blocks from the river, in the heart of what was once Troy’s banking district. At the north-east corner of the street stood a four-story red brick and limestone mid-19th century building which had been built for the Mutual Bank of Troy. A large brass plaque was affixed to the building’s side. Baltimore guided his guest to the wall so that he could read it. “Here was begun on April 27, 1860, the Rescue of Charles Nalle, an escaped slave who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act.” John Nalle turned to his friend in shock. “What? I’ve never heard a word about this,” he exclaimed. “Well, my friend,” said Garnet Baltimore, “Have I got a story to tell you!” He guided him to a shady spot by the wall. “It all starts in Culpepper County, Virginia.” He was not your usual black cat. They are usually the stuff of Halloween decorations – of medium size, sleek and lean, with long thin tails. This cat was large and fluffy, technically still a short-hair, but with thick black fur with brown undertones. Brushing him often yielded enough fur for another cat, with an endless supply in store. He had a large skull, big yellow eyes and a slightly flattened face and nose, no doubt the result of unknown Persian ancestors. His paws were as oversized as his head, and his tail was a long fat triangle; broad at the base and tapering down to a paintbrush of fur. He was from Ohio, Oberlin to be exact. He was rescued in town by a student at the Oberlin School of Music. The singer named him L’il Bat, after a character in the opera Susanna. He must have been the cutest little fluffy black kitten. When bass-baritone Daniel Okulitch moved to NYC several years later, with his cats, he was singing the role of Schaunard in Baz Luhrmann’s Broadway production of La Boheme. This was the beginning of a very successful opera career, with touring and appearances across the country and in his native Canada. This is where I come in. I was still singing at the time and was an avid reader of an opera chatroom called the Opera Forum. In addition to chats about various aspects of singing, readers could also ask for help or services. Daniel was looking for a cat-sitter. I had just lost one of my two cats, and Mookie, the surviving one, was depressed. I thought temporarily having two more cats around would cheer him up and help him get over losing his buddy Felix. Plus, the guy was paying. I offered to take them. Every year about this time, I pen an article about Troy’s Enchanted City Steampunk Festival. This year’s festival is this coming Saturday, September 15th, on the streets of downtown Troy. Last year’s fair took place in Riverfront Park for the first time. While it was great to have room to spread out and wander around, it was removed from the street level, and lacked the energy and vitality that being on Troy’s main streets brings. This year, it’s back on the street, sharing part of downtown Troy alongside the famous Troy Farmer’s Market. By the middle of the 19th century, Americans realized that parks provided a spot of nature and greenery amidst an increasingly busy and industrialized world. Many men, women and children worked six days a week, and never had the time or resources to get away. Yes, parks were beautiful, but they were also very important for mental and physical health. Cities that wanted to thrive began looking for space and funding for public parks.

People from everywhere flocked to parks like Manhattan's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park. Postcards of the parks were circulated throughout the country as tourists marveled at the wonders. Many cities contemplating the development of their own parks came to see both, and many others to take notes. When the city of Troy decided to establish a new park on the top of what was called Warren Hill, one of the highest points in the city, they too looked downstate to Brooklyn for inspiration. Prospect Park gave the park’s designer some great ideas to incorporate in Troy’s own park. They also cribbed the name. |

AuthorMy name is Suzanne Spellen. I've been many things: a writer, historian, preservationist, musician, traveler, designer, sewer, teacher, and tour guide; a long time Brooklynite and now, a proud resident of Troy, NY. Archives

February 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed