|

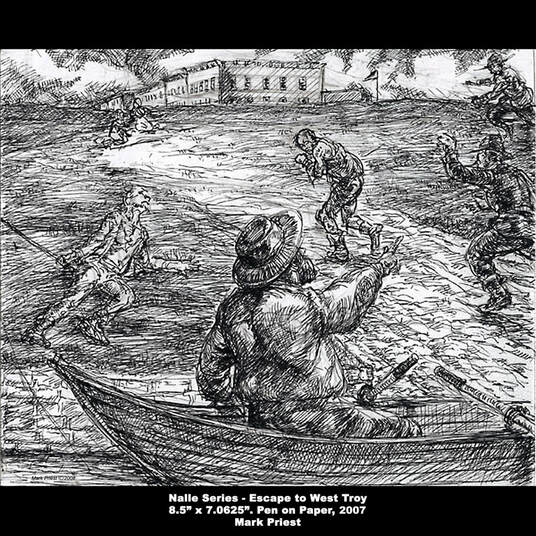

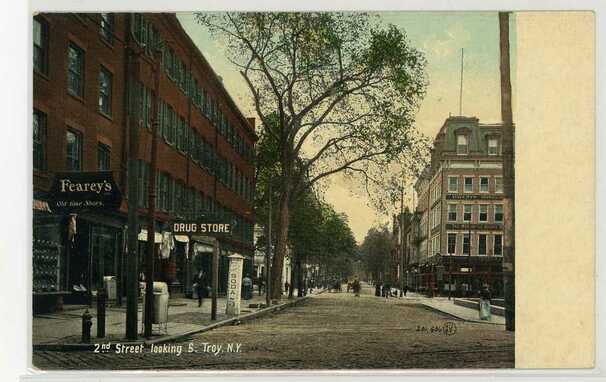

Concluding the story of Charles Nalle: the rescue and aftermath. The slave catcher, Wall, and the Deputy Marshall stopped Nalle in the street, and arrested him. Before he knew what had happened, he was manacled and taken back to the reluctant U.S. Commissioner, Miles Beach. When Charles didn’t return from the bakery, Uri Gilbert’s son went out to look for him. He went to his landlord, William Henry, but Henry had not seen him since that morning. It was not like Charles to disappear, and William Henry, who knew Nalle’s history, suspected the worst. Henry was a member of the Vigilance Committee, a Troy abolitionist group that aided escapees in secret and spoke out against slavery and the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law in public. He made some inquiries, and quickly found out that Charles had been arrested and was in the hands of a slave catcher. With no time to waste, he sent the word out and told his people to get ready to act. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was a fine piece of evil legislation, with some especially nuanced advantages for the slave holder written into it. Not only could a slave owner or his or her representative come north and snatch a suspected escapee off the street, that person had no rights, and no recourse to prove that he or she was not a slave or was not even the person they were looking for. There were usually no photographs or sketches, as enslaved people were usually not the topic of art or photography. There were only vague descriptions which would match any number of people. This was fine with the slave catchers, because they got a bounty for each fugitive returned South. If they had the wrong person, it really didn’t matter, who would believe a slave? When Charles Nalle was brought before Beach, all the paperwork had already been prepared by Henry Wall, filled out days before he had even been captured. Nalle was not allowed to identify himself or testify on his own behalf or give any names for potential witnesses. His fate had already been decided. All that was needed was the formality of having Wall and the informer, Horace Averill, stand before the Commissioner and declare that Nalle was the fugitive Negro slave who had unlawfully escaped his enslavement, and run away. His lawful owner, Mr. Hansbrough, had just stepped off the train to meet them, and the fugitive would be taken back to Virginia, where he belonged. Charles was being held in the cells in the basement of the Commissioner’s office, in the Mutual Bank Building, on the corner of State and First Streets. A prominent Troy attorney named Martin I. Townsend quickly volunteered to be his lawyer. He went to the Commissioner’s office to represent his client, but it was already too late, the paperwork had been signed. Townsend rushed out to prepare a writ of habeas corpus to present to a judge, and thereby get a stay. The Rescue of Charles Nalle One of the most effective warriors against slavery was the great Harriet Tubman. She was a tiny little woman, no taller than five feet tall. But she was as tough as nails, and as fast and resourceful as a ninja. After escaping from slavery herself, between 1849 and the dawn of the Civil War, she singlehandedly traveled back and forth from the plantations of the South to the Canadian border more than nineteen times, leading captives out of slavery. Over three hundred people directly owed their freedom to her, and she faced capture and certain death every day as they traveled north along the Underground Railroad. Her own family members were among the first people she shepherded to freedom, and some of them settled in upstate New York, in Auburn, and in the Albany-Troy region. Part of Harriet Tubman’s success lay in the fact that most people didn’t believe that this diminutive woman could possibly be the scourge of plantation owners everywhere. Aside from the Abolitionist community, no one really knew what she looked like, and they never caught her, or came close to finding out her identity. She was a ghost, blending in as a field hand, appearing as an old woman, or a nursemaid or humble servant. For those she helped to freedom, and those who helped her as operatives on the Underground Railroad, and supported her financially and in spirit, she was simply called “Moses.” In the spring of 1860, she was slated to speak at an Anti-Slavery rally in Boston. She was traveling east from Auburn to Boston, so when she reached the Albany area, she decided to take some time to visit a cousin, John Hooper, in Troy. Not only was her cousin here, but she knew William Henry, the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, Stephen Myers and everyone else in the Capital Region Abolitionist network. She was a general to their army and was right at home in Troy. Charles Nalle was brought before the U.S. Commissioner, who released him to his vindictive half-brother and his slave-catching agent. The slave catcher had fastened heavy iron manacles to Charles’ wrists, and planned on leading him out into the street, with Averill and Hansbrough right behind him. They intended to get in a wagon which would take them to the nearby train station, and then head back to Virginia. But word of Charles’ capture had spread throughout Troy. Members of the Vigilance Committee had quickly gathered up a sizable crowd. Troy did not like slavery, or those that practiced it. John Brown had been very well received here, and after his execution, his long funeral cortage had stopped in Troy. Contempt for the Fugitive Slave Act was strong. People had also gotten to know and like Charles Nalle, and they were not going to simply allow him to be taken away. As the crowd outside of the Commissioner’s office grew, they had a secret and powerful ally in their midst. “Moses” was in the crowd, and she and the Vigilance Committee had a plan. Martin I. Townsend, the prominent Troy attorney, tried to get Nalle released, but the legal system was stacked against him. He left the U.S. Commissioner’s office and made his way through the growing crowd, on his way to the courthouse to obtain a writ to stop the extradition. According to the Troy Times’ account of the story, published the day after the event, the police were afraid to bring Charles down, as it seemed all of Troy was in the street. While they waited, the Commissioner allowed several townsmen into the office, one at a time, to speak to Charles and offer him encouragement. A tiny elderly and infirm black woman in a large yellow sunbonnet also pushed her way upstairs. The officers thought she was a relative and let her stay. It was Harriet Tubman, who was not as old or infirm as she pretended to be. Across the street, members of the Vigilance Committee watched from a house’s upper window. If they could see Harriet’s bright bonnet, through the hallway windows, they knew Charles was still in the office upstairs. The group stayed in the room for so long that some were beginning to think that Nalle had been taken out by another exit, but Harriet’s bonnet was still visible. At one point, Nalle had been seated by a window. When no one was watching, he managed to throw open the sash with his elbow and tried to climb out of the window. The crowd went wild with encouragement, but his heavy chains hindered him, and he was dragged back into the room. William Henry, Charles’ landlord and friend, stood before the crowd and made an impassioned speech about freedom and a man’s right to self-ownership. He told them how Nalle had been brought before the Commissioner shackled as a prisoner whose only crime had been in stealing his own body. He said that Nalle had been condemned to be taken away from his home, his friends and his employer in Troy to be again imprisoned on a cruel southern plantation where he would no doubt be tortured and killed for the crime of wanting to be free. Could the people of Troy, he asked, permit this good and intelligent man to be so deprived of liberty, a liberty they so freely had in abundance? Would they let a bounty hunter, a vile and low-down slave-catcher who trafficked in human misery, and his employer, a slaveholder from Virginia, win the day? Would they allow Charles Nalle, a man many of them knew and liked, to be dragged back into slavery? The good people of Troy roared “No!” According to another account, offers were made to buy Charles from Hansbrough, who initially agreed to $1,000, and when that was matched, upped it to $1,500. Someone in the crowd yelled, “Two hundred dollars for his rescue, not a cent to his master!” The crowd roared its approval. It was now getting late into the afternoon. At 4 pm, attorney Townsend returned with his writ, which demanded that the city marshal bring Nalle before Judge Gould immediately. Whether they wanted to or not, the parties involved had to go down into the street and face the crowd. Deputies were dispatched to make a path. As they went down the stairs, one deputy tried to move the aged Harriet out of the way. He even offering to help her downstairs, if she was unable to do so herself. Feigning decrepitude, she just shrugged off the help and stood her ground. The deputy moved on, coming out into the street to clear a path through the crowd, which was now ready for something to happen. The marshal, two deputies, Averill, the slave catcher Wall, Hansbrough and Charles Nalle came down the stairs. No sooner had they passed, Harriet threw off her decrepitude, rushed to the window, and shouted, “Here they come,” to the Vigilance Committee watching for her signal across the street. The party came out of the door. Charles Nalle stood before Troy, according to the papers, a tall handsome white-looking man, weighed down by the heavy chains on his wrists, surrounded by two deputies. His half-brother Blucher Hansbrough was right behind him, the resemblance so strong, it was hard to tell them apart. The crowd of Trojans, black and white, surged towards the group. Harriet Tubman ran out of the building, pushed one of the deputies aside and wrapped her arms around Charles Nalle’s chained hands, refusing to let go. They were both knocked down, and the mob surged around them, pushing and fighting with the deputies, Wall and Hansbrough. While they were down, surrounded by her people, Harriet took off the bonnet and tied it on Charles’ head. But not everyone in the crowd was set on freeing Charles Nalle. There was also a contingent that had pro-slavery sympathies, or perhaps just liked a good fight, because the scene began to grow more violent, with fights breaking out throughout the crowd. The combatants surrounded Nalle and Harriet, who had still not let go of him. They rose, and with his face covered, the master now became the slave, as Hansbrough was mistaken for Nalle, and both parties struggled around them all. Charles and Harriet were knocked down again. Charles was cut and bleeding heavily from the manacles, and Harriet, who never let go of him, had her coat torn from her, and they had even torn off her heavy boots in the melee. The Troy Times reported that Harriet shouted, “Give me liberty or give me death,” which encouraged the mob even more. The chaos was such that over two thousand people were in the streets, many of them just fighting, many more intent on getting Charles Nalle out of there. The deputies had lost Nalle. As they struggled to find him, Harriet and the Vigilance Committee managed to spirit him from State Street, through the crowds, down to the Hudson River, a distance of several blocks. He was supposed to get into a rowboat commandeered for the occasion, but when the rower saw the crowd surging towards the river, he panicked and ran. Nalle made a mad dash for the nearby public ferry and jumped on board. The boat took him across the river to West Troy/Watervliet. As fast as all of this was, the telegraph was still faster. Warned that the fugitive was coming across the river, the police were ready in Watervliet. Charles ran from the ferry, a man still in chains, bleeding and battered, running up the street away from the river. Harriet had not been able to get on the ferry, but was on the one right behind it, but by the time she and her followers got to Watervliet, perhaps only ten minutes behind Charles, he was gone. A Second and Final Rescue As Nalle pulled himself up the west bank of the Hudson, and began running along Broadway, the authorities were waiting for him. Exhausted, drained of adrenaline, and seemingly without hope in sight, he was taken away without much resistance. The West Troy authorities took him to a brick building near the ferry dock, to a judge’s office on the third floor, awaiting the arrival of Troy’s Marshall and his deputies. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Nalle, a second rescue was about to take place. Harriet Tubman had never lost a passenger in her entire career as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She, along with the members of the Vigilance Committee and the citizens of Troy, wasn’t about to start losing one now. The ferryboat carrying Harriet and three hundred other people docked in West Troy only ten minutes behind him. Harriet and the others ran from the ferry up the river bank, but Charles was gone. A group of children playing by the river pointed the way, “He’s in that building,” they said, pointing to the brick building by the docks, “Up on the third floor!” The crowd composed of blacks and whites, men and women, surged ahead, approaching the panicking officers of the West Troy constabulary. They rushed up the stairs, and the West Troy police began firing into the crowd, hitting two men, who fell backwards on the stairs, injured but not dead. The crowd kept coming. The police were outnumbered, and in the chaos Harriet Tubman and her men rushed into the room and took the exhausted and bleeding Charles out of the room and down the stairs. According to legend, the five-foot Harriet Tubman, herself battered from the assault in Troy, took Charles in her arms, and like a mother with her child, carried him down the stairs. When they reached the street, a stranger rode by on a wagon. He stopped and asked what the commotion was. When he heard the story, he jumped down from the wagon and offered it to the rescuers. “This is a blood horse,” he exclaimed, “Drive him till he drops!” Today, a commemorative marker, erected in 2009, notes the place where the second rescue took place. Harriet, along with a small number of supporters and at least one of Charles’ friends, jumped in the wagon, and headed west on the Shaker Road, towards Schenectady and the Erie Canal. They stopped in Niskayuna, just outside of Schenectady, where Charles’ chains were struck from his wrists, and the bruised and battered man was hidden until he was recovered enough to keep going. He moved northwest to Amsterdam and stayed in hiding for several months. Meanwhile, his employer, Uri Gilbert, and his friends raised $650 to purchase his freedom from Blucher Hansbrough. Charles Nalle came back to Troy a free man and a hero. He was able to contact his wife Kitty, and three months later, she and their five children joined him in Troy, where they lived through the Civil War years, until they moved away in 1867. The family moved back to Washington DC, to be near relatives on both sides. There, Charles was employed by the Post Office. He died in 1875 and was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery. He never told his children anything about his life before his freedom, or the rescue in Troy. The Aftermath After going back to Virginia after his close escape in Troy, Blucher Hansbrough, Charles Nalle’s erstwhile half-brother, returned to his plantation just in time for the nation to go to war. The Civil War changed the course of his life forever. During the winter of 1863 to 1864, over 20,000 Union troops from the Second Corp of the Army of the Potomac camped on his land. They took over his house as headquarters and marched from there to the Battle of the Wilderness. After the war, his holdings were a shadow of their former glory. In 1873, Blucher Hansbrough died. He did not leave a valid will, only piles of debt, most of it incurred long before the war started. The vile betrayer, Horatio Averill, barely got out of Troy alive. The crowd was ready to inflict great bodily harm upon him, but he managed to get into a coach and get out of the city. He was never welcomed in Troy again. He later claimed that he had not betrayed Charles Nalle and offered up several other names as the likely betrayers. The Troy papers did not buy it, and for many months later, were still printing accusations and letters from irate readers. In 1875, after the announcement of Charles Nalle’s death, the accusations came back to haunt him. By that time, he had moved with his brother to West Virginia where they made a fortune in the coal business. He sold his interests, moved to NYC and managed to reinvent himself, becoming a State Supreme Court judge. He returned often to his hometown of Sand Lake, in Rensselaer County, where he had first met Charles and gained his confidence, those long years ago. He and his brothers built a resort hotel and community nearby and today, the town of Averill Park bears their name. He died in 1887, but before he went to his final reward, the Averill Park development was foreclosed on. He died leaving his brother and sister-in-law with the mess. Uri Gilbert continued his great success in the carriage and coach business. He became mayor of Troy between 1865 and 1870 and was known in the city as a great philanthropist as well as an important businessman. He was on the boards of the orphan asylum, hospitals, banks and educational institutions. He died in 1888 at the age of 79. His house at 189 Second Street still stands and is part of the city’s Washington Park Historic District. Several people from Troy were charged for some of the actions that took place in Troy on April 27, 1860. They were all acquitted, and no one was happier about that than the prosecutors, the sheriff, his deputies and all officials associated with the case. The Troy paper noted that “this, we hope, is the last of the series of prosecutions in respect to the rescue. So far, they have proven a farce, and it is likely they will do so to the end of the catalogue if they are continued. We have information, which we believe is based on reliable authority that henceforth they are to cease.” Harriet Tubman, of course, was one of the greatest heroes of the 19th century. She told audiences who gathered to hear her story, "I was conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger." During the Civil War, her uncanny ability to slip past the authorities made her a valuable scout, and she became the first woman to lead an assault during that war. When she wasn’t scouting, she was a nurse for the Union Army. Despite her service to the Union, and to the country at large, she was denied pay and recognition by the U.S. Army until 1899. She joined the women’s suffrage movement and worked alongside Susan B. Anthony and others. As she grew older, her fame spread, but she lived most of her life in dire poverty. Her farm in Auburn was paid for by friends, and she often had so little money that she was forced to sell her livestock to buy train tickets to her many speaking engagements. By the early 20th century, she was sick, still suffering from the headaches that plagued her entire life, caused by a blow to the head as a child, while still in slavery. She died of pneumonia in 1911 and was buried with full military honors. Today Harriet Tubman is one of the most famous and admired women in American history. The city of Troy continued to grow after the Civil War, reaching its peak in population and wealth by century’s end. In 1908, the people of Troy placed a memorial plaque on the old Mutual Bank Building. celebrating the rescue as one of the ten most defining moments in Troy’s history. As Garnet Douglass Baltimore ended his story, he looked at his childhood friend, who had tears running down his face. Named for Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass, he had only been a baby, less than a year old when the dramatic rescue took place. John Nalle was only a child of four on that day, still living in Washington with his mother and sisters. Of his parent’s eight children, he and one other sibling were the only ones still living. His father had never told them the story of his rescue. He knew his parents had been slaves, but he had never heard any of the stories regarding his mother’s perilous existence in Washington, his father’s flight to freedom, or of the Great Rescue, or his parent’s reunion. He never knew that the announcement of his father’s death from heart disease in 1875 had been reported in Troy. One paper proclaimed that Charles Nalle had “caused more stir in this city than any man has before or since.” Another paper was more circumspect. The Troy Daily Times wrote in their obituary that Nalle was “highly respected and although his life was one of turmoil and persecution up until the time when he received his freedom, he has since enjoyed the blessings of peace and of the emancipation that was given to his race. He has numerous friends in this city who are among his sincerest mourners.” John Nalle was fascinated by his father’s story, and planned to write a book, but sadly, died soon afterward. His family never took the project further. A year later, the Sons of the Revolution, a civic group, replaced the plaque with the bronze marker. That plaque was repaired and restored in 1987. It marks the place where Troy’s people decided that a man’s life and freedom was more important than the letter of the law. Today, the story of Charles Nalle and his rescue is taught in Troy’s schools, and is still regarded as one of the city’s most defining moments. Walking tours, guides and many Trojans point proudly to a moment in the city’s history when it fought against injustice. “Here was begun on April 27, 1860, the Rescue of Charles Nalle, an escaped slave who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act.” The rescue of Charles Nalle is a proud part of Troy and Watervliet history. The local newspaper, the Troy Times, carried an eyewitness account, which was picked up by other papers. Years later, the story was told again and again, In Troy, and in Auburn, the home of Harriet Tubman. All three cities are very proud of what occurred on and around April 27th, 1860. My research for this story comes from the Troy Times, the Auburn Citizen, and information gathered on various websites, much of which is gleaned from the scholarship of the late Scott Christianson, the author of a very highly researched and detailed book on the subject called “Freeing Charles: The Struggle to Free a Slave on the Eve of the Civil War”. Mr. Christianson’s book was especially helpful with details about Charles Nalle’s early life and the people and places that made up his world. Stephen Myers' home is still standing. Today it's home to the Underground Railroad History Project organization. They provide important research and information about the Capital Region's participation in the Underground Railroad and the Abolitionist Movement. The organization's founders, Paul and Mary-Liz Stewart, and their members and staff have assembled an important collection of papers, artifacts, and other historical data, archiving this important data which is not just African American history, but American history. We should all know about Myers, Garnet, Nalle, Tubman and many, many more. Please check out their website for activities and information. https://undergroundrailroadhistory.org/. The Rensselaer County Historical Society is also a repository of information. They are located in Troy, and can be found at https://www.rchsonline.org/

1 Comment

Linda Hardwick

2/16/2019 10:34:13 am

This is a great story. I want to do the casting for movie! On another note, I went to Emma Willard and it wasn't taught there in the 60s. I wonder if it is now. And if not, you should give them hell.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Suzanne Spellen. I've been many things: a writer, historian, preservationist, musician, traveler, designer, sewer, teacher, and tour guide; a long time Brooklynite and now, a proud resident of Troy, NY. Archives

February 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed